The radio in navigation

Radio transmission has revolutionised navigation. Even though some traditional instruments may still be used, radio-based equipment has supplanted sextants, flags and lighthouses, allowing vessels to communicate with each other and the land, to know their precise position at any time, and to detect obstacles even in darkness or fog.

From the end of the 19th century, Marconi used marine environments, where radio signals are scattered much less than on land, for long-distance transmission experiments. The maritime authorities, both civil and military, confirmed their interest in technological innovation during this period. Marconi collaborated with the Italian Royal Navy, which made the La Spezia naval base and the Carlo Alberto battleship available.

Meanwhile other scientists and industries were also developing radio communication technology. Following installation of the radiotelegraph on ships from the end of the 19th century, radar and the radiotelephone came into use in subsequent decades, and radio beacons and other geographic positioning systems were installed, culminating in today’s satellite technology.

Guglielmo Marconi

Marconi (b. Bologna 1874 – d. Rome 1937) was passionately interested in physics from childhood, particularly the research on electromagnetic waves that had just been published in Europe. Experiments were oriented towards practical applications, whose economic potential he could sense.

In 1895 he was the first to transmit radio signals to a receiver placed more than a kilometre away. This made long-distance communication possible, initially with Morse Code, which was already used in telegraphic signalling over wire.

Development of this technology subsequently made it possible to transmit voice, images and all the essential bits of data of everyday life.

In 1896 Marconi found support in England for continued research into transmitting over ever greater distances, and won the first patent for wireless telegraphy. He immediately founded the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company for the manufacture and installation of transmitting and receiving equipment for use on land and aboard ship.

In 1901 he succeeded in transmitting across the Atlantic Ocean, and won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1909.

Among the exhibits on display is the key of the Elettra telegraph used by Marconi in Genoa to give the signal that activated the public lighting of Sydney, Australia, on 26 March 1930.

The Elettra

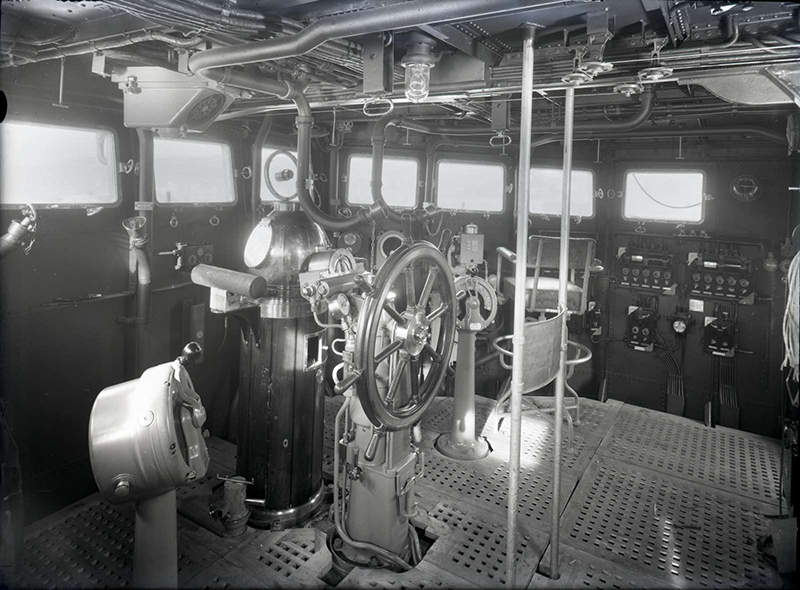

In 1904 the Archduke of Austria Charles Stephen of Habsburg-Teschen (1860–1933), then Vice Admiral of the Austro-Hungarian Empire Navy, had an elegant yacht built in Scotland, naming it Rovenska after a locality in Veli Losinj where he had a residence. The Rovenska was 67.40 metres long with two masts and a 1000 hp steam engine. It was sold after a few years and had several more owners.

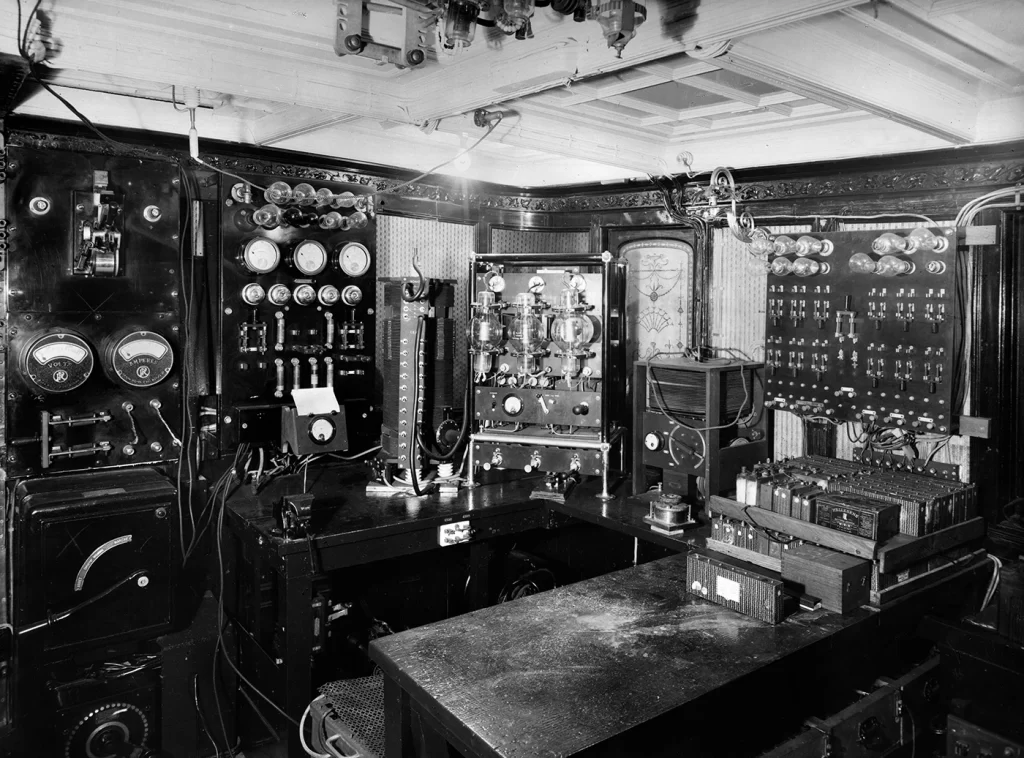

Guglielmo Marconi bought it in 1919, had it restructured, equipped it as a floating laboratory and renamed it “Elettra”.

The inventor and industrialist used it to perform experiments and stage events that attracted worldwide public attention.

Aware of its historical and symbolic value, the Italian State acquired the ship and its contents in 1937 following Marconi’s death.

Events in the Second World War brought the Elettra to Trieste. The German navy requisitioned it for war use. The local authorities managed to save the equipment that Marconi used in his experiments, plus other furnishings and objects, some of which later reached the Sea Museum.

On 21 January 1944, in Dalmatia, the ship was hit and partly sunk. The wreck was not recovered until 1962, with various parts of it being sent to scientific institutions in Italy.